BY SHELLIE TAYLOR

Family Bibles are among the most valuable, and yet somehow forgotten, research tools for genealogists. They are also rare and becoming rarer still as time progresses.

The Genealogical Society of Iredell County (GSIC), whose collection is housed at the Iredell County Public Library, holds several unique family Bibles, all of which have been digitized, catalogued, and placed in archival boxes for preservation. The library is making every effort to fully digitize these rare materials to make the information accessible to researchers.

The Genealogical Society of Iredell County (GSIC), whose collection is housed at the Iredell County Public Library, holds several unique family Bibles, all of which have been digitized, catalogued, and placed in archival boxes for preservation. The library is making every effort to fully digitize these rare materials to make the information accessible to researchers.

Years ago, the GSIC also compiled information from family Bibles and published them in a volume which is available to view in the library’s Local History Room. The information gathered from society members in that book is incredibly valuable.

My favorite part of scanning these magnificent books is the little treasures that are found within their pages. I have found funeral cards, obituaries, dried flowers, handwritten notes, photos, and so much more. Many times, I have discovered that a Bible kept and passed down through the generations will tell a story of the evolution of that family. Library staff have also attempted to learn more about the families who owned these Bibles by conducting research. The stories that have been uncovered remind us why we do what we do to preserve history.

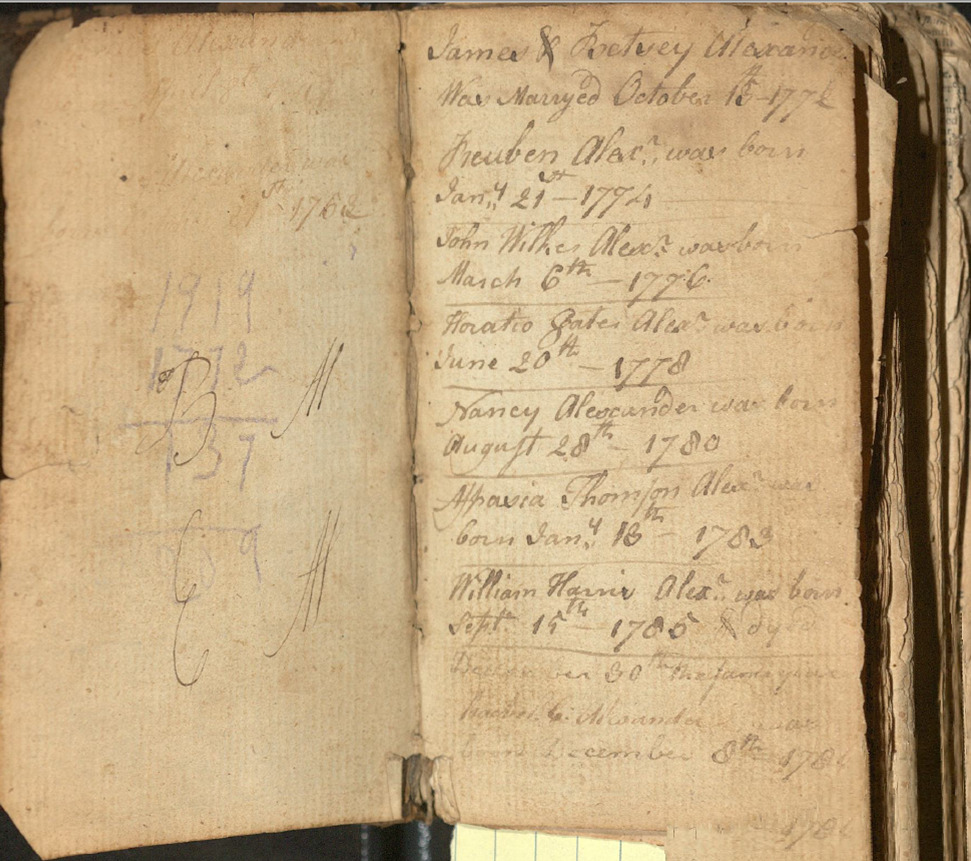

The earliest Bible in the collection belonged to James Alexander and is dated 1778. The publication date of this Bible predates Iredell County by ten years. This Bible crossed multiple state lines with the family. James Alexander was born in Pennsylvania and married his wife Elizabeth in that state on October 15, 1772. There are several sources, most notably Find A Grave and Ancestry, where users report the couple’s oldest son as James Alexander, born in February of 1772, eight months before his parents’ marriage. The Bible makes no mention of a son named James. The oldest son listed is Rueben Alexander, who was born in 1774. Are we to believe that a family would omit a child’s name simply because his birth was illegitimate? It is more likely that the James born in 1772 actually belongs to a different set of parents. In fact, other sources report him as being the son of David Alexander and Margaret Monroe. This is a wonderful example of how family Bibles can provide genealogical information for researchers.

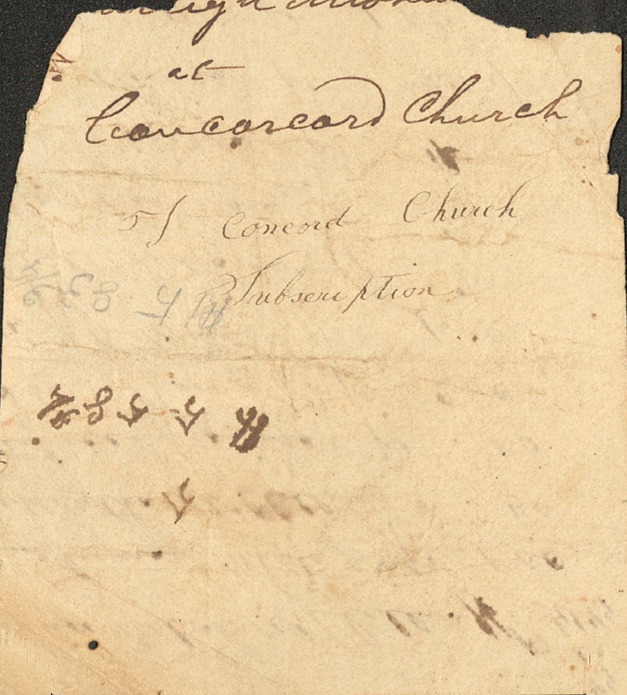

James and Elizabeth Alexander’s daughter, Nancy, married William Morrison in 1807. Their daughter, Elizabeth, married William Curtis McLelland in 1838. Their Bible is also housed in the collection. The McLelland Bible, published in 1820, has several loose pieces of papers throughout its pages spanning multiple generations, including a notice from the sheriff dated 1849, a list of attendees for what looks like a class from 1886, and a blank note from a 1944 calendar. There is also an undated note with the words “Concord Church” written on it. Could this connect the family to Concord Presbyterian Church? Perhaps the list from 1886 is a Sunday School attendance list. The Alexanders and McLellands mentioned in these Bibles are most likely buried at Concord so it is safe to say they attended. The Morrisons were founding members of the congregation when it formed in 1775. In fact, the descendants of several of these families are listed in the earliest extant records of the church that the library has on microfilm from 1896.

Inside the Turner family Bible, published in 1873, a photograph was found. It looked to be of nurses and soldiers from World War I in a hospital setting. No writing was inscribed on the back, so Joel Reese, Local History Librarian, set off to find what he could on the photo and its connection to the Turner family.

The Turner family Bible was originally owned by William Elias Turner and his wife Victoria Kallum Turner (born 1848 and 1849, respectively). They were married September 26, 1872, and they had a large family. Their oldest son, Charles, founded Turner Manufacturing in Statesville. Their second son, William Benjamin Turner, was born September 8, 1886. Willie, as he was known to friends and family, ended up serving in World War I. According to transport lists, he was aboard the Aquitania, which departed from New York for France on June 8, 1918. He was part of the medical team that was shipped out. He returned to the U.S. on April 23, 1919, from France on the U.S.S. Manchuria. Something interesting is reported on his service card that might give an indication about his experience on the front. He is listed as a cook and ambulance driver, the latter of which would definitely have carried him onto the battlefield to retrieve wounded and dying soldiers and transport them to a medical facility. His service card reports that he sustained no injuries, which is not uncommon for medical personnel, but that he was 15 percent disabled. How could he be disabled without being wounded? Reese has concluded that based on previous extensive research on Iredell’s World War I veterans that Willie Turner had most likely been exposed to the poisonous gases so common on the French battlefields.

Willie would spend the rest of his life recovering from and living with the effects of the gas used on American, French, and British troops by opposing forces. In 1921, the local newspaper reported that he was coming home from an operation in Charlotte and would need to return to receive additional treatment. He would never marry nor would he ever leave his parents’ home, except for hospital stays. His obituary mentioned that he worked for his brother’s manufacturing company as his health allowed, indicating that he attempted to stay active throughout his life. In the 1940 census, he is listed as an inmate (term for patient) at the Veterans Administration Mountain Home in Johnson City, Tenn. He would later reside at Oteen Hospital in Buncombe County, where he would spend his last days. He died at the age of 63 on April 15, 1950. His death certificate reported the cause of death to be “pulmonary tuberculosis reinfection type, far advanced” and that the period between onset and death had been eleven years. It was a rare thing to endure the effects of tuberculosis for eleven years, but Reese has seen it often on the death certificates of World War I soldiers. When looking at their obituaries, he has found mention of the soldiers having been gassed in the war. The connection is obvious: someone exposed to poisonous gas would have weak lungs and be highly susceptible to communicable lung infections such as pneumonia and tuberculosis. Although he lived for more than 30 years after the end of the war, William Benjamin Turner eventually became a casualty of World War I. He rests in the family plot of Oakwood Cemetery in Statesville.

Although we are unsure which person in the photo is Willie, we are confident that he is in there somewhere. It is a peculiar thing to find in a family Bible, but it is further proof that these Bibles hold treasures that we would never expect to stumble upon.

Shellie Taylor is the Local History Program Specialist at the Iredell County Public Library.

Thank you for this info. Good to have this resource available.